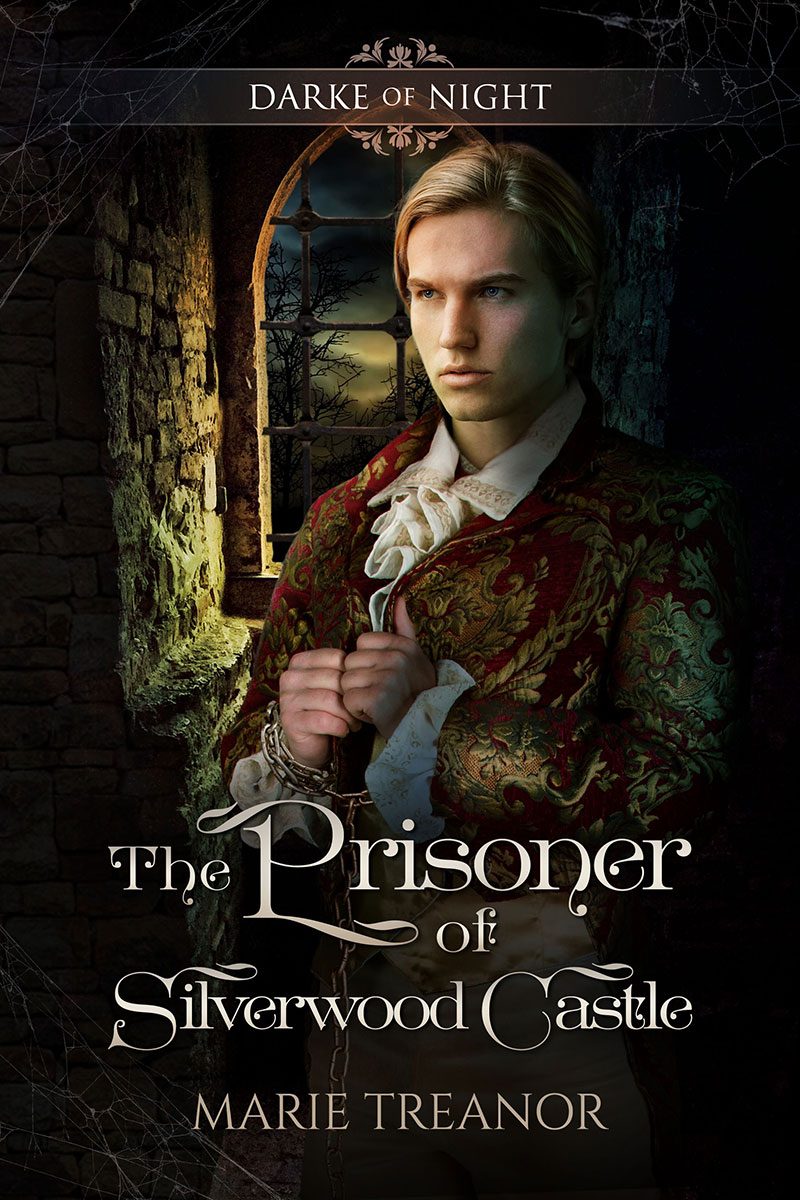

Darke of Night, Book 2

Who is the prisoner chained in the castle tower?

Lady Guinevere (Guin) Harvey would rather be writing gothic tales of intrigue and adventure than dancing attendance on her sister, the newly married Duchess of Silberwald. Until they arrive at Silverwood Castle, a place of such gothic perfection that Guin is enchanted.

Ghostly groans and clanking chains lead her through old, misshapen passages to a cell where she meets the odd but charming Kasimir, who’s kept chained like an animal – and who could be a figment of her vivid dreams, the ghost of a dead, mad prince, or just a political prisoner no one wants to talk about.

But the castle holds many secrets. What beast makes such soul-chilling cries in the night? Why does she have such strange dreams whenever she drinks the tea? More than anything, why is she falling so easily under the prisoner’s spell?

Guin summons the medium Barbara Darke, but by the time Barbara arrives, Guin can no longer distinguish dream from reality, friend from enemy. Even with all Barbara’s unique talents, they have to face new dangers before they finally discover the terrifying truth.

You can buy this book at:

Chapter One

My first sight of Schloss Silberwald changed everything. It rose up out of the mist in a fantastic array of turrets and towers, beautiful, mysterious, and just a little eerie. I was enchanted.

“It’s like a fairy-tale castle,” my sister Augusta said in clear relief. Well, as its new mistress, she must have had concerns about the establishments she’d come to preside over. And for Augusta, having married her prince, behold, the fairy tale continued.

For me, the castle seemed the embodiment of all my favourite gothic novels. I shivered with delight and allowed the last of my resentment to slip away.

Up until that moment, despite my interest in all the places we’d passed through and visited across Europe, I’d harboured the grudge that I’d been forced to accompany Augusta, the unwilling sacrifice upon the altar of her fairy-tale marriage to the ruling Duke of Silberwald. For once the ring was on her finger, Augusta had suddenly panicked that, splendid as her marriage was, she was about to journey to a foreign country where there were no guarantees that anyone but her husband and his aide spoke any English. And so I, as her last remaining unmarried sister, however plain, however small an asset to her consequence, and however much I irritated her, had been cajoled and browbeaten into accompanying her.

The cajoling and browbeating had taken many forms, and the perpetrators included all my sisters, their husbands, my brother the Earl of Alnwick, and a certain government minister. I’d dug in my heels and resisted from some perhaps foolish fear that I would be merely absorbed into Augusta’s life when I so desperately wanted one of my own making.

It was my stepsister Caroline who’d finally persuaded me. “Guin, it doesn’t have to be a punishment,” she’d said in her kind, yet humorous way. And she never shouted. I’d always appreciated that in Caroline. “This is an opportunity for you! To travel, and see the places you’ve dreamed of, to explore and discover and learn. If you truly want to be a writer, this is necessary for you.”

I allowed that she had a point, and with ill grace gave in. “I don’t see why she had to marry a German prince,” I’d muttered. “I blame the Queen for making them fashionable.”

Of course Augusta hadn’t just married any old prince. Leopold was the ruling duke of his sovereign state, tiny as that might be. And I had to admit our journey had been fascinating, although too quick for me to do the exploring I truly wished to. But now, at last, as we drove up to Schloss Silberwald—Silverwood Castle—, I was glad I’d come.

The smooth, well-maintained road wound around the hill. With a sense of rather delicious anticipation, I watched the castle grow bigger and more real as we drew closer, passing at high speed through a traditional village which I saw only as a blur.

There was a brief delay at the heavy iron gates, guarded by two splendidly unformed soldiers, and then we drove into the grounds. The horses picked up speed, as if anxious to be home, and Augusta and I peered out the carriage window to catch every glimpse we could.

The castle was built of pale grey stone. We clattered through a wide, ornately carved archway into a spacious courtyard, and the horses slowed and halted. Augusta straightened in her seat, unable to keep the smug smile from her face.

“It’s bigger,” she said, “than Alnwick Park.” To Augusta, this meant progression. In fact, it was nothing like the Georgian pile we’d grown up in. This was an actual castle. I itched to run inside it and explore.

But, of course, there were formalities to endure. The duke stepped down from his own carriage while one of the liveried servants opened the door to ours and let down the steps. The duke advanced towards us.

I didn’t care for my new brother-in-law. Although he seemed to suit Augusta very well, and he was never anything other than polite, I found him…cold. Not yet forty years old, His Highness Prince Leopold, Duke of Silberwald, had a full head of brown hair, receding at the temples in a distinguished manner. His controlled, expressionless face was pale, divided by a thin, haughty nose, down which he liked to look at lesser mortals, and graced by a thin-lipped mouth, a square chin, and eyes that weren’t quite fishlike.

He bowed and personally handed his bride from the carriage in the kind of stately gesture Augusta most admired. I wondered what, if anything, lay beneath his civil pomposity and also how she could bear to be married to such a man. A horrible and quite un-maidenly vision of their intimacy flitted through my brain and was banished with desperate haste.

Button, Augusta’s wide-eyed English maid, and I followed her with the help of only the liveried servants. I was happy to let Augusta bear the brunt of the formal welcome. A carpet had been spread from the duke’s carriage to the main entrance to the castle, and it was lined with formally dressed noblemen and women in brightly coloured silks and lace. They all bowed and curtseyed deeply as the duke progressed with his new bride. He paused occasionally to present the favoured to Augusta, who carried off the ordeal with an enviable air of entitlement.

I felt like grabbing Button’s hand for mutual support, though fortunately I restrained myself. In fact, since all attention was on the happy couple, we blended into the duke’s lesser entourage and no one paid us any attention at all. Which left me free to gaze around at the formidable entrance way. Close to, the castle was more military than fairy tale, reminding me that its primary purpose had always been defence. In fact, it had been besieged during the late revolution, which the present duke had put down with such ruthless efficiency.

The entrance hall was magnificent—all ornately carved stone and wall torches with a wide, curving stone staircase sweeping upward on the far side. I shivered with delight, feeling a story of profound atmosphere coming on: a pale figure gliding down those stairs, the ghost of some long forgotten lady… Oh yes.

Reluctantly, I trailed after everyone else into a disappointingly modern, though still splendidly massive hall, where Augusta was divested of her travelling cloak and, after a brief speech of welcome from some dignitary or other, was invited to visit her own private apartments.

Augusta graciously assented, and two of the finely dressed ladies stepped forward to accompany her. She would have sailed off without a backward glance at me, except that the duke suddenly seemed to remember my existence and looked around.

“Lady Guinevere?” he called.

I cringed. For although I rather like being called after a literary character, the name does not suit me. I am small, plain, short-sighted, and bookish, and I had more than once, during my dreadful “season” in London, overheard sniggering at the very idea that knights might vie for my attention.

“Stay with me,” I advised Button, who was clearly lost in this sea of nobility, and pushed through in my sister’s wake.

“My sister-in-law,” the duke introduced me grandly, still in English. “Lady Guinevere Harvey, who attends the duchess.”

Attends? No one had called it that before they’d shoved me into the coach with her. Prickles stood out all over my body. I felt like a hedgehog. But I bit my tongue and trailed after the duchess.

* * * * *

I forgave her all over again when I saw my bedchamber. It was in the old part of the castle, and it had a low, vaulted ceiling and bare, unplastered stone walls on which hung some ancient and very dusty tapestries. Since it was growing dark, I lit the lamp and stood on my trunk to reach the little window catch. I had to wrestle with it to make it open, as if the cobwebs were trying to hold it shut. Although my sisters would not have approved of the housekeeping—and in fact, even I considered a little dusting to be in order here—I liked the little chamber far more than Augusta’s grand, luxurious apartments. It seemed I had maligned my brother-in-law the duke, and he understood me much better than I had thought.

In perfect charity with him, I unpacked my clothes, seized a clean gown to wear for the rest of the evening, and put the rest away in the oak wardrobe which looked a little out of place but was at least useful. I washed my face in the bowl provided, gasping at the coldness of the water, then brushed and repinned my hair, and, with difficulty, found my way back to Augusta’s apartments.

She had a bedroom, a dressing room, a cosy dining room, and a large sitting room. They were all utterly feminine, with no sign of the duke’s accoutrements, so I could only assume his rooms were elsewhere. Perhaps through one of the two doors at the end of the sitting room. I wasn’t sure I would care to live like that if I was married. Provided I liked my husband, of course, and I had long ago decided that nothing except actual love would induce me to marry anyone, however rich, powerful, or influential. Fortunately, my brother the earl seemed to be content with those commodities he’d already gained through my sisters’ marriages, Augusta’s being very much his trump card. So I doubted I would have to fight very hard for my independence. Once I got away from Augusta.

We were to have a comfortable “family” meal. Augusta and I sat down with the duke, his younger brother Prince Heribert, and Augusta’s two ladies-in-waiting.

“It is late, and we are all tired from travelling,” the duke pronounced. “So, I thought this cosy supper would be an excellent thing, to help you, my dear, relax into your new abode and become acquainted with your new ladies, who will do everything in their power to help you settle in.”

The younger of the two ladies seemed already to be lost in admiration of Augusta, who did, I admitted, look even more beautiful than usual in her new surroundings. I suspected she was getting her own way in everything.

The elder of the Silberwald ladies, the elegant, grey-haired Baroness von Gratz, took the trouble to smile at me kindly and to speak in English.

“You are a good sister to travel so far with the duchess. Such devotion.”

I suspect both Augusta and I looked completely baffled by that interpretation.

“We thought it best,” I mumbled.

“I hope your bedroom is satisfactory? We are a little overcrowded at—”

“I love it, thank you!” I said with enthusiasm.

It was the baroness’s turn to look baffled.

“Sehr schön,” I said to avoid confusion. I’d been teaching myself German from a book on the journey, trying out my pronunciation on several of the duke’s servants and hotel staff as we travelled. I was quite pleased with my progress.

“Schön,” the baroness repeated faintly.

Well, I thought it beautiful.

As I set about my food—I was starving and it smelled delicious—I was aware of the duke’s gaze upon me, approving, perhaps, or reassessing. I didn’t much care. I was looking forward to exploring his castle.

We were to stay here for several days, I understood, before travelling on to the capital city of Rundberg where the duchess would be formally received and the duke could attend personally to matters of state, including, I gathered from the brief conversation he conducted in German with his brother, some continuing unrest.

I was intrigued by this. I’d been reading up on Silberwald, and it wasn’t all good, despite the more liberal reforms promised by the duke’s government since the revolution. However, even I could see this was not a great time to bring up such matters. The politics was more of a private, almost breathless aside in the midst of the main event which was, I thought cynically, sucking up to the duchess.

Prince Heribert seemed genuinely dazzled by her. The ladies-in-waiting, even the baroness, hung on her words. The duke watched with approval, so far as I could tell. I ate the excellent supper with gusto, wondering how soon I could escape and explore. I wasn’t remotely tired.

After supper, the duke stood, raising his wineglass, and proposed a toast to his duchess. After which he and his brother both kissed her hand and departed.

“I took the liberty,” the baroness said, “of ordering tea to be served in your highness’s sitting room. I understand this is your custom.”

“Thank you,” Augusta said, standing. “Then let us go and partake.”

One cup, I thought happily, as I tripped after the others into the sitting room, and then I’m off!

A maid was just leaving a heavy tea tray on the occasional table, which was surrounded by an array of chairs and a sofa.

Augusta draped herself languidly on the sofa and waved one hand in my direction. “Guin, you see to it.”

“Oh no, please let me,” the baroness said, pressing my shoulder as I made to stand again. “The weary travellers should rest.”

The tea was duly poured, milked, and passed by the younger lady, whose name seemed to be Hilde. The porcelain cups were exquisite, eggshell china, smooth as silk against my lips. The tea itself wasn’t great, but the Silberwald ladies seemed so pleased with their achievement that I pronounced it excellent. Augusta made no comment.

I drank it quickly and said good night. Augusta frowned at me, as if I should have asked her permission. Then, when I laughed, she waved me away with an irritated flick of the wrist. She had Button and her adoring new ladies in waiting.

The passages back to my own chamber had grown chilly, making me shiver, so I resolved to collect a shawl before I went about exploring.

I found a maid in my room, closing the shutters and the window.

“Pardon me, my lady,” she said hastily in her own language. “It gets cold at night.”

“Of course. I shouldn’t have left it open. I was admiring the view.”

The maid gave a nervous smile as she clambered down from my trunk and hurried towards the door.

“What else is along this passage?” I asked. “More bedrooms?”

“Oh no, my lady. Only yours. Beyond here, the old part of the castle isn’t safe.”

“You mean it’s falling down?” I wasn’t sure if I was more intrigued or appalled.

“Bits of it. Many collapsing walls, I believe.”

“You believe?” I pounced. “Haven’t you seen for yourself?” Nothing very short of certainty of death or severe injury was going to keep me from my explorations. “Haven’t you seen for yourself?”

“Oh no, my lady, I don’t go down there. No one does.”

Then how did they know it was dangerous? “Why not?” I asked.

“Well it’s haunted, my lady, for one thing.”

Of course it was. I shivered with delight. “Really?” I took a step closer. “By what? Have you ever seen a ghost there?”

“No, I never have,” the maid admitted. “But then, I’ve never been farther than this room and wouldn’t either, if I could help it. You hear strange noises in the old wing.”

“Like what?” I asked avidly.

“Oh, banging, tortured cries like souls in torment. So faint you can barely hear them, but still, when it’s dark, they echo sometimes. Makes your flesh crawl.”

“I imagine it might,” I said, impressed.

I had a load of other questions to ask, but as I opened my mouth, the girl seemed to shake herself and said, “Will that be all, my lady?”

“Oh yes, thank you.” Since she was clearly in a hurry, I’d find out for myself. It would, I assured myself, be more fun that way. So I let the maid go and set about my preparations. Before dousing the lamp, I lit a candle from it, setting it on the bedside table while I dug a shawl from the wardrobe.

But I yawned as I wrapped the shawl around my shoulders and languidly pushed my spectacles more comfortably onto my nose. On impulse, I sat down on the bed, trying it for comfort, and realized I was more tired than I’d thought. Although I didn’t mean to close my eyes, I did.

* * * * *

The silhouette of a candle flame flickered up the wall, peaceful and mesmerising. I lay on my bed, fully dressed. The glow from my bedside candle lent an extra eeriness to my delightfully gothic room; but since a certain fuzziness clung to the edges of my vision, I knew I must be dreaming.

A sound like a human cry, long and plaintive, echoed from the bowels of the castle, both thrilling and chilling to the blood. Just as the maid had described it. But at least my dream was one of those interesting ones, where you seem to be able to control what happens next.

So I rose from my bed, and as I’d meant to do in reality before I fell asleep, picked up the candle, and sallied forth into the ancient corridor. Instead of going towards Augusta’s room, I went the other way, heading into the haunted depths of the old castle. My dream gave the walls a slightly strange shape, almost like a tunnel. When I thought about it, my bedroom had changed to be a bit like that too.

There weren’t many doors in the passage, and the ones I tried were locked. Well, the maid had said the castle beyond my room wasn’t used. I seemed to walk an awfully long way through the thick gloom, which my candle barely pierced. When I did espy a turning, I veered left in the hope of some variety. Eventually, I found myself in a large, empty hall with an enormous stone fireplace. The stonework was crumbling, but some of the carvings were still intact—ornate leaves and intertwining branches, angelic figures balanced on curls of stone.

If I were the duchess, I’d dine here… Even in my dream, my imagination populated the hall with colourful characters from the past, Renaissance scholars, artists, soldiers, and princes…or Teutonic warriors and their ladies, defending their castle from all comers. Oh but I could tell some stories of this room…

Wishing it were real, I moved across it with my candle, appreciate the strong, silver moonlight that spilled in the row of windows along one wall. A spiral staircase, well worn by centuries of feet, led upward from the far end of the hall. I climbed, holding my candle high to see where I was going. The first door I came to was locked, so I climbed on, wondering if I was in one of the towers I’d seen when we arrived. Since I was in control of the dream, I decided to make it so.

“What’s more,” I murmured to myself as I came up to another closed door, “this one will open.”

Although it was heavy and seemed to be made of iron, it did indeed open when I pushed hard, leading me into a small room with one rough wooden chair and a table with a book on it. Even in my dream, my heart beat a little faster, because there was no dust on the book or on the table. This part of the castle was used.

Well, it was my dream, and too many disused corridors and empty rooms were boring.

From the corner of this room, a narrower set of stairs led upward. I followed them, coming to yet another door, also of iron, but with a small square hole cut in it and covered by a grill. Since the grill was just above my eye level, I couldn’t see in.

I pushed at the door, but it remained determinedly shut.

“Whose dream is this anyway?” I said aloud. “Open.” I pushed again, harder, but the door was clearly locked. “Damn.”

Inside, something clanked, like metal against stone. I shivered with delight. Clanking chains! This was much better.

“Damn what or whom?” enquired a deep, male voice from within, in perfect English.

A thrill ran through my bones from my toes up. “This door,” I said. “It won’t open.”

The chains, or whatever they were, clanked again.

“Perhaps you could unlock it for me?” I said hopefully.

“Sadly not. I don’t have the key.”

I frowned. “You mean you’re locked inside? Or is there another way out?”

“There’s always a way out.”

“Oh.” I set down my candle, meaning to take off my shoes and stand on top of them to try to see through the grill. “Who are you?”

There was a pause. “Kasimir,” said the voice, as my candle shone on a low stool on the far side of the landing. “Who are you?”

“Guin,” I said, placing the stool by the door and standing on it to peer through the grill. Inside was pitch-dark, so I bent and retrieved my candle.

“Just Guin?” Metal clanked again as I raised my candle to the grill.

A young man in a torn shirt and faded trousers with holes at both knees sat on the edge of a truckle bed, hands raised against the pale light I shone on him. He seemed very large for the tiny room, but otherwise, I couldn’t see much more than a mop of shaggy blonde hair and two big, if slender hands with chains dangling from both wrists. He lowered them slowly to reveal a lean, fine-boned face with glittering blue eyes, lips parted, perhaps in surprise. He was handsome enough to make even my determinedly hard heart beat faster. Dreams could be very pleasant…

On the other hand, manacles bound his wrists, a thick chain running between them and up to a bolt in the wall above him.

“Goodness,” I said, impressed and appalled all at once. “I really did hear clanking chains. You’re a prisoner.”

“Yes. Are you?”

“Lord, no.”

He stood, tugging at the chains so that he could take a step nearer the door. My heart lurched, but the chains pulled him up short. Even in the dim light, his wrists looked red and raw.

“Oh dear,” I said. “I’ll bring you ointment for your wrists.”

He peered at the grill, leaning his head from side to side as if trying to see me better. “You will? Why?”

“They look sore.”

He stepped back and glanced at them. “I suppose they are.” He sounded vaguely surprised. “Are you my new keeper?”

“Your keeper?” The phrase sounded odd; perhaps it was the translation. “No. I’m the duchess’s sister. Why are you in here? What did you do?”

He seemed to think about that. “I don’t know that I did anything.”

“Perhaps you’re a political prisoner,” I said. After all, it would explain his educated speech, his knowledge of English. “Were you involved in the revolution in ’48?”

His eyes seemed to flash. It looked like pain or desperation. And then, making me jump in startlement, he leapt into the air, seizing the chains between his hands and tumbling upside down. He swung himself over the bed and, bracing his weight against the tense chain, began to walk up the wall in his bare feet. Beneath the thin shirt, muscles bunched in his arms and shoulders. He must have been very strong.

“What are you doing?” I asked curiously.

“Distracting myself to see if you’re an illusion.”

I blinked. “Actually, you’re the dream.”

“I am? Why would you bring ointment to a dream?”

“Good question,” I allowed. “Instinct, I suppose. Your wrists do look sore.”

He flopped back down on the bed, and the chains clanked against the wall. “Then again, why wouldn’t I dream of a beautiful girl who just wants to be kind to me?”

“You can’t see me very well from there, can you?” I said. “I’m afraid I’m not beautiful, but I will still bring you the ointment.”

He leaned back, drawing his knees up under his chin. “If you wanted to be very kind, you could bring me a file instead. One of those sharp, narrow ones I could use to kill my gaoler after I’d cut my chains with it.”

My blood chilled. “Would you really do such a thing?”

“Oh yes, I think so.” He frowned. “I’m sure I’ve done it before, though perhaps that was just wishful thinking, since I’m still here. Or it might have been someone else…” His rather stunning blue eyes, which had glazed over as if with the effort of memory, came back into focus on the square hole. “I’m talking myself out of the ointment too, aren’t I? Don’t worry.”

“I won’t when I wake up.”

“Hmm.” He leaned his head to one side. “The duchess’s sister. British-style democracy is very popular here. Leopold married into the liberal English earl’s family in order to curry favour with our own liberals. Is the duchess very liberal? Are you?”

I stared at him. “Augusta isn’t political at all.” Although I knew it didn’t really matter what I said, since I was only dreaming, I felt obliged to add, “She will, of course, share and support her husband’s views.”

“Will you?”

“I don’t have a husband.”

“But if you did, would you keep your own opinions?”

“I have it on good authority I’m too opinionated ever to be married.”

The prisoner smiled at me, an unexpectedly dazzling smile that actually caught at my breath. “You could always marry a man who had no opinions of his own and tell him what to think.”

“I have no desire to marry a vegetable,” I retorted.

“No, it would be dull,” the prisoner agreed, and with one of his sudden movements, sat forward on the bed again. His muscles rippled in the candle’s pale glow, and my stomach lurched in a pleasurable kind of way I wasn’t used to. It came to me that he no longer seemed very dreamlike. The fuzziness seemed to have gone from the edges of my vision.

Surreptitiously, I touched my face with my free hand. I was wearing my spectacles. In fact, I remembered putting them on before I left the room, before I fell asleep, in fact.

“What if I’m not dreaming at all?” I said aloud.

“Why should you imagine you’re dreaming? Why would you dream about me?”

“Because your…your prison is exactly the kind of thing I’d put in my story. I’m afraid I’m addicted to imagining and writing stories. And everything looked…off, fuzzy, like looking through the wrong lens or those strange mirrors they have in fairground stalls.”

His eyes didn’t blink as they regarded me. I thought I saw pity there. “You drank the tea. You shouldn’t drink the tea.”

My mouth fell open. “What?” After all the trouble the baroness had clearly gone to, not drinking the tea would have caused an international incident.

But the prisoner had apparently moved on. His head turned toward the tiny slit window, slightly cocked to one side.

“You should go now,” he said. “Hurry, or they’ll see you.”

“Who will?”

He sprang up, wild-eyed, lunging so furiously in my direction that I stumbled back off the stool and nearly dropped my candle.

“Run,” his voice commanded as the chains jolted him to a cruel halt. I heard the clank and his panting breath. “And don’t tell anyone you were here.”

I grasped my shawl in my free hand and planted my foot on the first step before his words really penetrated. “Why?” I demanded. “Why shouldn’t I tell anyone?”

A breath of laughter drifted out of the prisoner’s cell. “Because I’m dead.”