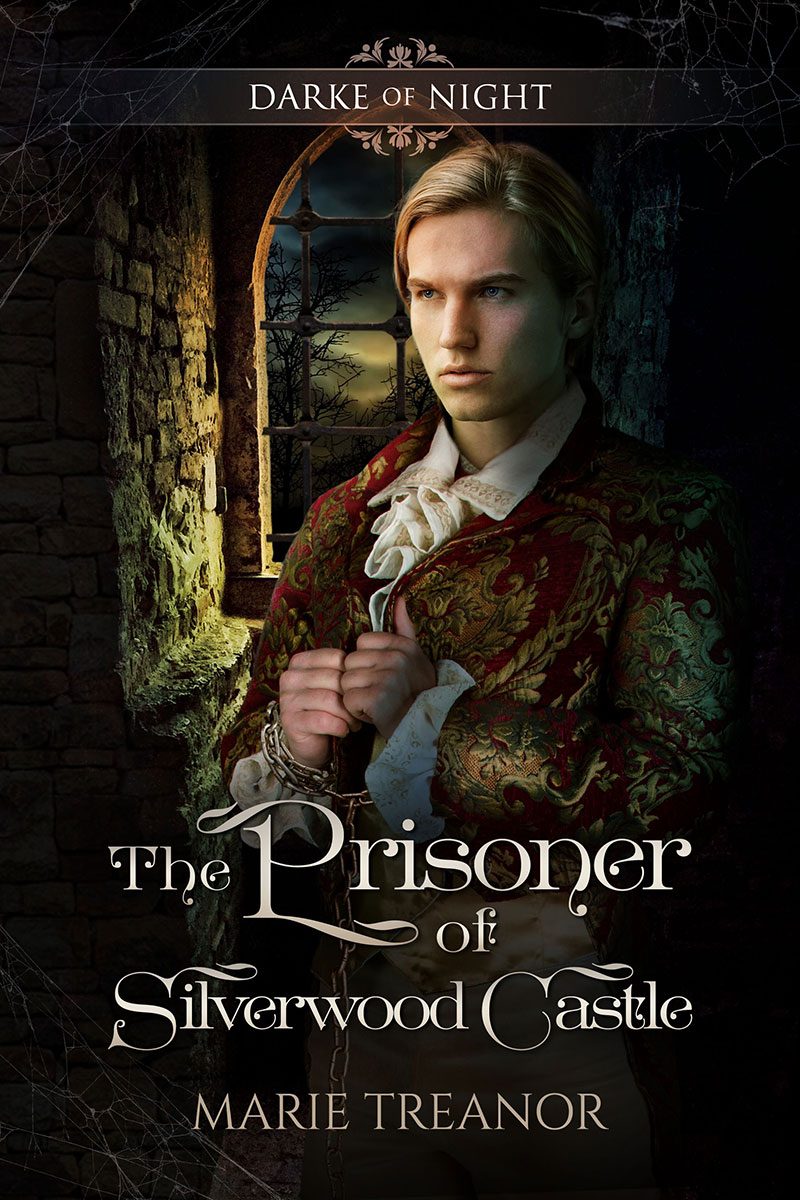

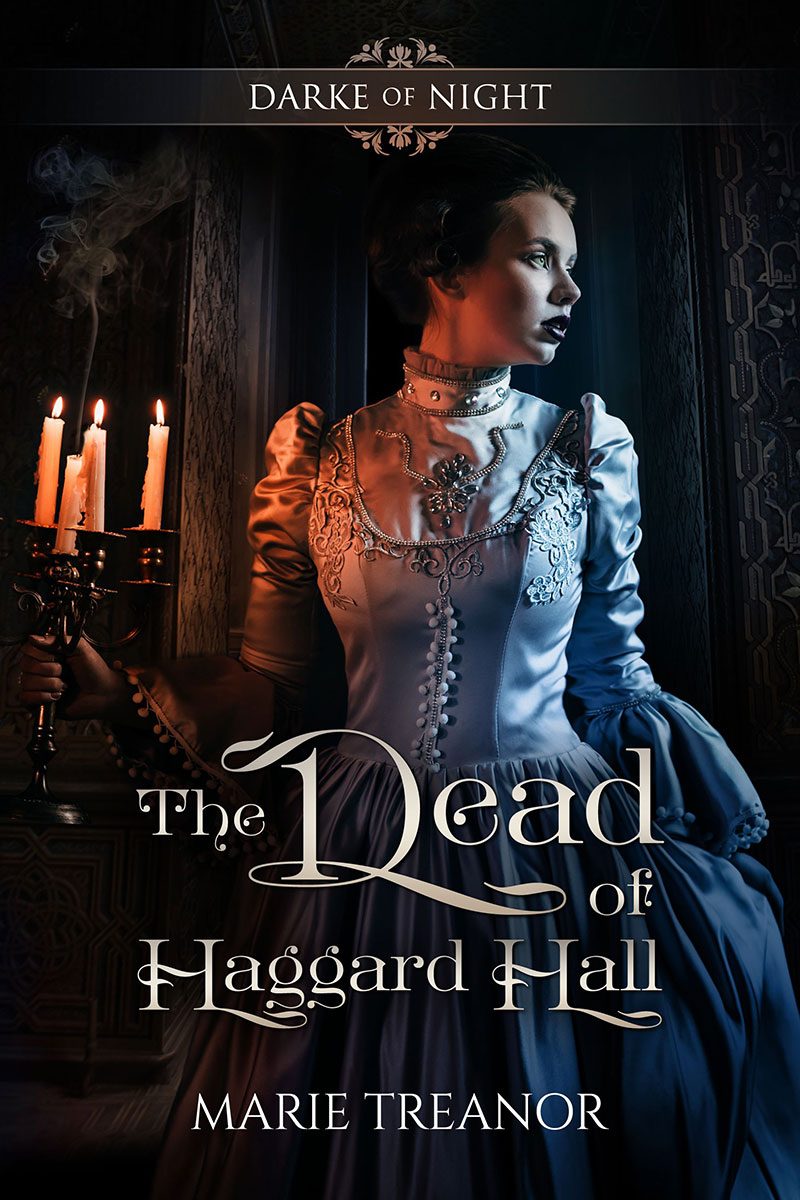

Darke of Night, Book 1

A gothic romance of temptation and possession

Barbara Darke – schoolteacher, vicar’s widow and natural medium – reluctantly accepts the position of companion to her former pupil Emily, now the bride of young Sir Arthur Haggard. At Haggard Hall, Barbara finds her friend beset by ghostly noises and unexplained deaths.

In a maelstrom of dark spirits and wicked emotions, Barbara battles the family’s disapproval to lay Emily’s ghosts – both hampered and helped by Arthur’s sceptical cousin Patrick, who provokes and attracts her in equal measure. It would be a mistake to trust such a secretive, guilt-ridden man already suspected of driving his wife to suicide, if not of actually murdering her. And it could well be lethal to give in to her own desires, confused as they often are with the lusts of the dead.

But Arthur and Emily are in genuine physical danger from someone at Haggard Hall, and suspicion is falling on the man who haunts Barbara’s sensual dreams, Arthur’s cousin and heir, Patrick…

You can buy this book at:

Chapter One

I have never cared for public séances. Unfortunately, my mother is addicted to them, so I should have known that my one night spent with her in three months would include a summoning of the spirits for the delectation of the curious and the entertainment of the jaded in search of new experience.

“It looks like a fashionable evening party,” I said, peeking through her bedroom door to the adjoining drawing room where some dozen people in evening dress had already gathered. They were about equal numbers of men and women, a mixture of ages. Most had helped themselves to a glass of wine or lemonade from the table at the far end, which had been set with refreshments.

“No point in living in these rooms in this part of London and not having a party,” my incorrigible parent pointed out. She had been given the rooms for her own private use by the owner of the house, Lady Fairford, her most avid patroness of the moment. Lady Fairford was, in fact, in the drawing room welcoming guests. Only my mother could have induced her noble landlady to act as hostess for her while she primped in front of the ornate mirror.

“Won’t they be disappointed if the spirits don’t visit you? Or even if they’re too quiet and uninteresting?”

“They would be disappointed,” my mother replied with a complaisance that told me such a dull event never occurred. Of course it didn’t. My mother would supplement her undoubted gifts with as large a dose of fairground charlatanism as necessity demanded.

In the drawing room, a young, sad woman in expensive mourning was deep in conversation with a slightly nervous young man who seemed to be comforting her. Clearly bereaved.

I glanced back at my mother. Her eye caught mine in the mirror as she arranged the last curl. “Don’t give me that look, Barbara. I’m only too aware of my own shortcomings, but I truly couldn’t exist on a teacher’s salary. Or any such respectable salary! And frankly, with what I’m earning now, you don’t need to either. Why did the wretches at that ridiculous school dismiss you?”

I peered back out through my crack in the door. A couple of the fashionably curious arrived to be greeted by the fluttering Lady Fairford. Another figure propped up the outer doorway behind them: a tall man with black, unruly hair and a hooked, predatory profile.

An observer, although he looked somehow too dramatic for this to be normal behaviour. A little frisson of interest passed down my spine, taking me by surprise.

I said, “One of the pupils accused me of conducting a group séance.”

To my mother, this was no crime. As I let the door close on her guests and turned back to her, she held my gaze expectantly. Eventually, she asked, “Well, did you?”

“Of course not! But some of the girls had been asking about the dead and ghosts, and I tried to explain it to them. One had been recently bereaved. I felt sorry for her. I let them take me to a room where they’d sworn they saw a ghost.”

“And you saw it?”

I smiled ruefully. “It saw me. It was inside me before I could slam the door. I wouldn’t have had the girls witness that for the world.”

“Was it a nasty spirit?”

“No, it was lost and confused, but I still spoke with its voice and scared the girls half to death.”

“So they told on you?” My mother was gratifyingly outraged on my behalf.

“One of them obviously did. The headmistress explained to me that I had to resign or they would turn me off without a character.”

My mother abused the headmistress roundly, although her eyes lit up again almost immediately. “But perhaps it’s for the best, Barbara. You can live and work with me here. Imagine the scenes we’d create in partnership!”

I didn’t need to imagine. From adolescence onward, I’d known my mother and I should never live together.

“Fortunately,” I said, “I have another offer of employment. I refused at first, but now it seems I have no alternative—if I’m not to steal your thunder.”

My mother turned and stood up to assess me. “You would too. I know you’re joking, but your youth and your looks—”

“I am nearly thirty years old and dowdy!” She’d told me so on our last reunion.

“I didn’t mean that,” she said with a dismissive wave of one hand. “Your clothes are dowdy, a matter easily rectified now. But whatever you wear, you have an air, dear. A sort of smouldering darkness that might just be wicked—”

“For God’s sake, Mother,” I expostulated. “I am a vicar’s widow!”

“Priests are the worst,” my mother said outrageously. “Why do you think Gideon was drawn to you in the first place? The purity of your soul?”

I swung away, but I could never hide from her any more than she could from me. She caught my hand.

“I know,” she said, with just a hint of huskiness, quickly passed. “I miss Gideon too, and he understood: we’re not wicked, Barbara. But we can make use of the false perceptions of the ignorant.”

“That,” I said, “is what’s wicked.”

“Nonsense. We all have to earn a crust. Talking of which, what is this new employment of yours? It must be truly dreadful if you turned it down originally in favour of that awful school.

“The school was not awful,” I argued. “I liked teaching; I was good at it. And I liked my pupils. Most of them. And clearly some of them liked me. One, a girl who left last year and is now married, asked me to be her companion.”

“Who is she? Whom did she marry?”

“Emily Jansen. Wealthy family—live mostly in India—caught a baronet’s son for her. A younger son when the engagement was announced, but the older brother died suddenly, and Emily is now Lady Haggard.”

My mother regarded me as if I were a new and bizarre species of insect life. “And you turned down the opportunity to be her companion? Living in luxury with the best of everything? Attending the best social events with the best families in the country? Why?”

“I’ve never had a taste for luxury and I’d be bored in a day. Two,” I amended, because I liked Emily. She was a good-natured and intelligent girl with a lively sense of humour.

“And you hated the idea of dancing attendance on your former pupil?” suggested my mother, who is nothing if not shrewd.

“That too,” I allowed.

“Then the post has changed in some meaningful way?”

“No,” I retorted. “My circumstances did. I’ve told Emily this is temporary until we each find a better arrangement, but she wants me there now to leaven the company in her new home. She wasn’t brought up in that kind of society, and I think it overwhelms her. Apparently there is to be something of a constant house party in the family pile up in Yorkshire, to introduce her to all the extended family and friends, culminating in at least one ball.”

“An old country mansion?” My mother shivered. “Draughty.” She frowned. “Haggard, you say? Why does that ring a bell? Wasn’t there some unpleasantness at Haggard Hall a few years ago? One of them killed his wife…or was it suicide?”

I frowned. “Emily didn’t mention that. Surely it couldn’t have been her husband? I understand he’s barely older than she is.”

“No, it wasn’t the heir. A nephew or cousin or something.”

“She does mention a cousin of whom her husband is very fond. I don’t think Emily likes him.”

“That will be the scandalous one, the family black sheep,” my mother said with satisfaction. “The same man, I expect, who killed his wife. Apparently he is now having an open and scandalous affair with a baronet’s wife, right under the nose of her sick husband. It’s in all the worst rags.”

Which, of course, my mother read avidly. They were, often, her bread and butter.

“Vulgar,” I allowed. “Although not necessarily true.”

My mother shrugged that off. “Either way, Haggard Hall really doesn’t sound a great place for you, even as a favour. Perhaps you were right to turn it down. Wouldn’t you rather stay with me? Come, don’t answer until this evening is over. Let me introduce you.”

“I’m not dressed for an evening party.”

My indisputable statement hardly had the effect I’d expected. My mother’s face lit up, and she flitted over to the wardrobe where she pulled free two wispy black garments.

“I bought these for you—such fun! Look.” She held one up over her bright blue gown, spreading it so that the bluer could be seen rather charmingly through the fine black lace. “You can wear colours again for evening events and, since you insist, still be in mourning with this worn over the top. There is a fine silk one too. And the beauty is, they will look like different gowns depending on what you wear beneath. Isn’t it a wonderful idea?”

Before I could reply, the black lace garment was over my head and my mother was arranging it over my grey gown. It fastened close in over my breasts to my waist and from there hung loosely over the swell of my gown. She was right. It did transform my drab day gown into an evening dress—a modest evening dress, perhaps, but at least it fitted me perfectly.

Although actually, she rather missed the point of my dull gowns, which, after two years, were less to do with mourning Gideon than with my profession and my lack of funds to replace them with anything better.

“See? Try it with the red. And the lilac—”

“No,” I said. “I will come and meet your friends, but I will not take part in your séance.”

“Barbara.” She chucked me under the chin as if I were still ten years old. “When have you ever had the choice?”

Since I’d learned to feel the stronger spirits coming and knew to get myself out of the room.

It didn’t always help, but at least I suffered in privacy, which was what I had every intention of doing tonight if I had to.

There was a time when I had thought my mother a consummate actress. In fact, she didn’t adopt a stage persona for her public appearances; she remained herself, just…more so. She entered her drawing room full of guests, almost gliding beneath her wispy layers of clothing, smiling with genuine pleasure and anticipation, with just that hint of aloofness, of differentness that proclaimed she knew things lesser mortals didn’t. She did, of course.

Naturally, everyone stopped talking and turned to watch her entrance, even the man propping up the door into the hall.

“And here is our kind hostess!” Lady Fairford exclaimed, rustling forward to meet us. She almost pulled up short at the sight of me, and something passed over her face that looked almost like jealousy.

Yes, there is was. I could feel it. The atmosphere, or perhaps my mother’s excitement, was seducing away my layers of protection until all the swirling emotions emanating from her guests brushed against my consciousness like a physical caress. Lady Fairford’s burst of jealousy and shame; a wellspring of curiosity from just about everyone; varying degrees of hope and dread and excited anticipation; an outpouring of grief; the odd hint of scepticism…and one very large dose of scepticism with a coating of something rather like annoyance.

“Welcome, everyone!” my mother exclaimed, while I, with interest, sought out the fiercest sceptic. Such people could cause trouble for her. I suspected the interesting man by the door, but I could no longer see him for the people between. “I’m thrilled to be able to present to you my daughter, Mrs. Barbara Darke. Barbara, my kind patroness, Lady Fairford.”

Lady Fairford seemed relieved by our relationship, as if she’d imagined me some kind of rival for my mother’s affections or services. So while my mother mingled, drawing her throng of curious admirers around her like cloak, Lady Fairford and I exchanged polite greetings. I thanked her for her kindness to my mother and explained I was only staying one night on my way to new employment.

“Dear Genevieve told me you were a teacher. But I believe you also have your mother’s gifts?”

“Hardly,” I said, watching with tolerant affection as my parent held court. “My mother is unique.”

Since it was obviously where Lady Fairford wanted to be, I began to move towards my mother. Her ladyship came with alacrity and kept going when I slipped away to fetch myself a glass of lemonade and scour the crowd for my sceptic.

As I skirted the throng, which was broken into several smaller ones, like satellites around my mother, I cautiously opened myself further to their emotions. I felt my gaze tugged once more towards the open doorway to the hall. And there he was, my sceptic, looking right at me.

Something jolted inside me. I had been right. Full-on, his face was dramatic. Angular, almost bony, it was dominated by black, straight brows over dark, harsh eyes that concealed layers of turbulence and profound, conflicting emotions; a hard mouth with a sensual curve.

Tall, straight, and broad shouldered, his body gave the impression of being only loosely flung together. His dress was respectable and yet hung on him with such carelessness that it somehow suggested the entirely disreputable.

His unblinking regard washed over me in waves. Anger; constant anger. Curiosity and annoyance. He didn’t want to be here and yet needed to know what would happen.

Contempt, disbelief. And a sudden surge of lust that made me gasp and spin away from him in shock, for my own body flamed in wicked reply.

It was hardly the first time I had sensed such feelings directed at myself. It was a normal part of life, usually distant, unthreatening, and easy to ignore. But this man’s emotions ran deep.

Deep, damaged, dangerous, just the kind of man we didn’t need here. Just the kind of man I should avoid. My entirely worldly, physical response to him told me that. Even with my back to him, I could feel his eyes burning into me like caressing hands. And I wanted those hands. I needed them—on my breasts, between my thighs, everywhere—with a force that made me tremble. He would be a fierce lover, strong and demanding and exciting… I longed to be excited like that.

He wanted me. If I walked over to him now, I’d only need to smile and touch his arm and he’d take me away, to his own rooms, wherever they were, or to some anonymous, discreet hotel where we could spend all night in wild, sensual delights. Forbidden, delicious, without inhibition…

Maybe he’d exorcise the demon in me. Maybe I’d ease the demons in him.

But it would never happen. I needed my demons safely locked up, and I knew instinctively that this man spelled danger for me.

But I’d watch him for my mother’s sake, for I sensed he meant us no good.

As I walked back, I glanced to either side. He moved with me, following me, not just with his gaze but with his person, along the length of the wall, like a large, predatory cat. Or a wolf, perhaps. His lust enfolded me, teasing my own. But even over the space between us, interrupted by other guests who blocked my view from time to time, I caught the hint of contempt, the tinge of anger amidst the desire in his dark gaze.

Which made my temptation suddenly easy to resist. I halted and lifted one haughty eyebrow, allowing my own disdain for his undeserved judgment to curl my lip. I’d always found my stare and my eyebrow to be an infallible deterrent, but this man didn’t hesitate.

His lips curved upward, and as though he took my attention for an invitation, he swerved suddenly in my direction.

My breath caught in uncharacteristic panic. A new, fierce tug of sensual yearning told me I couldn’t be anywhere near this man, and yet I wouldn’t run. I refused to be despised when I’d done nothing to deserve it.

“Shall we begin?” my mother said, shattering the strange illusory bubble which seemed to have formed over myself and the sceptical stranger. “Those who would like to join in, please sit down at the table. Everyone else, feel free to watch and move around as you wish. All I ask is that you don’t interrupt. Sir, would you mind closing the outer door?”

She looked directly at my sceptical stranger. She might have seen our little byplay, or she might have sensed the same danger I did. On the other hand, he was nearest the door. I wondered if he’d be rude enough to ignore her request.

But my sceptic inclined his head. The gesture was somehow more mocking than gracious, but he obediently walked back and closed the door as she asked. Then he leaned one powerful shoulder against it and waited, apparently, to be entertained.

I found my own refuge by the bedroom door for escape purposes, and waited with resignation for the show. God knew there was enough emotion in that room to make it a good one.

And, of course, it was. Lady Fairford doused most of the candles until she left only an atmospheric glow, after which she sat at the table where a group of seven people joined hands and my mother summoned the spirits.

They didn’t just come; they surged. I fastened down my mental barriers, knowing I would need all my strength to keep them out. As always, along with those she named came the mischievous and the evil and the lost, all with their own agendas. We called them all spirits, but I was never sure all of them were. There are many things out there: wispy, elusive, formless things made from little more than emotion; ancient, nasty, cruel things whose only purpose seems to be to hurt or, perhaps, to find a way into our world at all costs.

Fortunately, although she has great powers to summon and attract spirits of all kinds, my mother does not receive them. She chats to them as if they’re all friends together at a tea party. I envied her that.

I held my barriers in place, shivering as I sensed the icy unease invoked by the uninvited. It never mattered how often I encountered them, they always had this effect on me, even though I knew they couldn’t hurt anyone in this world, except through me, and I knew how to keep them out. It was the first thing I remembered my mother teaching me as a child.

I held my hands tightly together over my stomach and dug my fingers into my wrists to hide their shaking as well as to keep my concentration.

My mother spoke to the spirits of a departed husband, a long-dead mother, and the child of the bereaved couple. Since I was so closed to them, I could only tell from my mother’s words which ones truly spoke to her. Once or twice she shook her head violently and I guessed the uninvited were whispering in her ear. As she passed on words and sometimes just impressions to her audience, emotions within the room intensified until, even cut off as I was, I could feel them almost physically, a powerful energy that made the candles flicker and caused the watchers to shift positions and look at each other with obvious unease.

Occasionally, I let my gaze wander to the sceptical stranger who lounged still in his doorway, hands in pockets, watching the proceedings with a slightly bored sneer curling his upper lip.

“We have other guests among the spirits tonight,” my mother said. “One of them is most anxious to speak to…Patrick.” My mother’s hopeful gaze swept around the table and on to the watchers behind. None stepped forward or raised a hand or otherwise admitted to being Patrick. I wondered if my mother had got her names muddled, or if we had a mischievous spirit in our midst—until her searching gaze landed on the sceptical gentleman who still lounged by the hall door, and stayed.

I knew then that she was being truthful rather than simply drumming up future business.

The sceptic, however, looked merely amused. He didn’t even straighten or take his hands out of his pockets. “Patrick who?” he enquired.

“You, sir,” my mother said firmly.

Without warning, the gentleman swept his gaze from my mother to me, as if pinning me to the bedroom door. Oh yes, his hard body holding me there, comforting, arousing. He wanted that; he was almost offering me that, and something deep and instinctive in me leapt to meet the unspoken challenge in his hard eyes—a sudden flame of excitement, or simple defiance, maybe.

I had little time to judge, for in my moment of inattention while I wondered if those harsh eyes ever softened in tenderness or laughter or passion, I had let down my guard, and something chill with evil shot into me like an arrow.

With the last of my will, I grasped the door handle behind me, turning it and throwing myself backwards. I might have managed it unseen by everyone except the sceptical gentleman, who may or may not have been called Patrick, except that my mother leapt to her feet.

“Stay back!” she warned. “No one go near her!”

By that time, I was stumbling backwards across her bedroom, giving in to the spasmodic jerking of my body because it made it easier to quell the sounds trying to come out of my mouth. The thing inside me was violent, jerking, malevolent, fixing on to the centre of my lust. It would have pleasured me if it could to achieve domination, but open as I am to temptations of the flesh, I have never been that desperate. Besides, my possessor was more repellent than truly frightening. I was stronger than it.

I think I was on the floor when my mother’s face loomed over mine.

“Away!” I gasped in a voice that didn’t sound like mine. “Go!”

At least she took me at my word now. And through my brief battle with the thing inside me, I was aware of the door closing behind her. I drew in my breath, gathering my strength, and spat out my uninvited guest like a fish bone that had been lodged in my throat.

It hurled itself at me again, but it was a feeble, disconsolate effort, easily repelled. If a spirit could have hung its head, that one did as it left me.

For a while, I simply regained my breath, calming by will the pulse beating between my thighs, and soaked in the peace and solitude of my mother’s bedroom.

I would not go back out there. By now, my mother would have been glad that some of her guests had witnessed my brief possession. It all added to the drama of the show. But I never liked anyone to see. And what bothered me particularly about this occasion was that he had seen. He’d witnessed my weakness and at least some of the ugliness that had possessed me. He wouldn’t believe it, of course. He would call it fakery and showmanship and go on his arrogant, contemptuous way, despising us. Despising me. And yet desiring me; I suspected he didn’t like that part.

Which didn’t, I reminded myself, staring out of the window into the darkness, matter one jot. I was leaving London tomorrow for Haggard Hall and Emily. What did the ignorant contempt of a lustful stranger matter to me? I’d never see him again. Thank God.

With unexpected weariness, I was about to turn away from the window to see if any of the clothes I’d left with my mother might be suitable for my new position with Emily, when I saw a man run down the steps from the house and stride off along the street without a backward glance. My hand stole up over my lurching heart. The party wasn’t over. I could hear it going on still in the drawing room, but I knew he was one of our guests.

He carried a tall hat, which he remembered to clap onto his head after a few yards.

Although I couldn’t see his face, I knew from the careless hang of his clothes and the loose limbed, wolfish stride that it was my sceptical gentleman. I wondered why he’d come.

As if he heard the silent question, he paused suddenly and glanced back over his shoulder, looking directly at the first-floor windows of my mother’s drawing room. Then his gaze moved on and found me.

I chose not to move, but it was possible I couldn’t have if I’d tried. Even through the glass and over several yards of space, something seemed to sizzle in the air between us, joining us like an imaginary fork of lightning. Curiosity. Desire. I had the oddest sensation that I couldn’t breathe, although of course I did, and too quickly for indifference.

The stranger’s lip curled. He tipped his hat to me with a civility that only emphasised his withering contempt. And then he strode off down the street.

I resorted to childishness and stuck out my tongue at his retreating back.