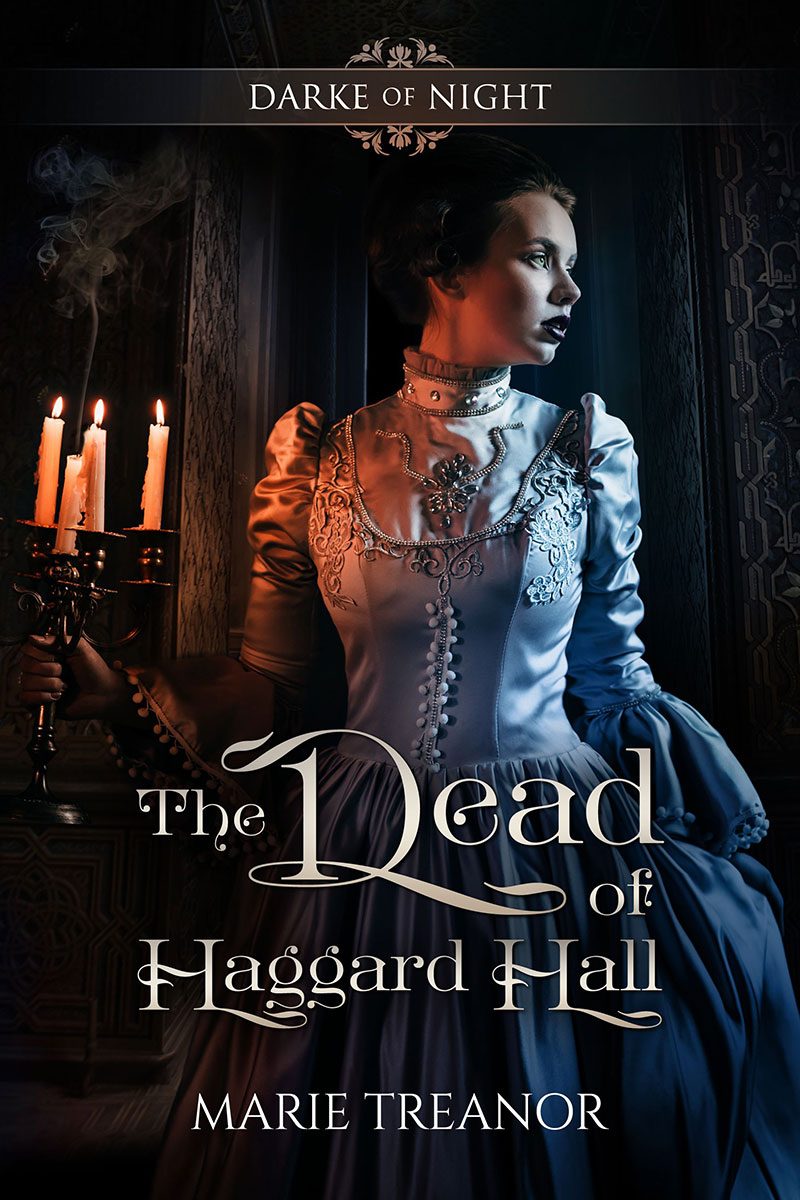

Darke of Night, Book 4

“You have no idea of the darkness that dwells in that house. And in him…”

Anna Goring is travelling to meet her fiance’s parents in Cornwall, when she and her family’s governess, the medium Barbara Darke, are forced to seek shelter for the night at Trellyn House – infamous for the terrible murders which happened there two years before. Their reluctant host is the man universally suspected, but never formally accused of the slaughter, talented young pianist Sir Salvador Carnwyth.

Despite his abrupt, ungracious manner, and the neglect of his once beautiful Gothic home, Anna is fascinated by her troubled host. None of Barbara’s warnings can prevent Anna falling in love with him. When she breaks her engagement and Carnwyth seeks her out in London to propose, her happiness is complete.

Until he returns to Trellyn House alone. Anna cannot wait for his summons but when she follows him, her welcome is anything but joyful. What is he hiding from her? Why does he lock himself into his private sitting room so obsessively? Who is it who plays the piano insanely in the middle of the night and makes the blood curdling cries? She knows instinctively it’s all to do with the murder of his family, the crime even his uncle suspects him of. And the danger isn’t over, from this world or the next.

You can buy this book at:

Chapter One

To a young lady who has travelled as much as I, the loss of a coach wheel is normally no great thing. It is an occasional annoyance that will not be mended by temper or hysterics. So, once Mrs. Darke and I had ascertained that neither of us was hurt, I simply climbed out of the listing coach into the road.

Of course, this was a slightly larger problem than I was used to. For one thing, I didn’t normally travel in the dark. For another, instead of being surrounded by my parents’ small army of servants, I had only Barbara Darke and John the coachman with me. Not even my maid, since my hosts were expecting many other guests and could not accommodate her.

Two of the coach lanterns had fallen off and gone out. Their remains crunched under my feet. By the lights that were left, I saw John at the horses’ heads, trying to calm them.

“You hurt, miss?” he called.

“No, we’re both fine,” I answered. “Are you? And the horses?”

John grunted, soothing the skittish horse nearest him with gentle strokes on her nose. “It’s only the coach needs mending. I think the front axle’s broken.”

“Well, you can’t do anything in the dark,” Mrs. Darke said philosophically. “How far are we from Penderran?”

“On these roads? God knows,” John said disgustedly. “We’d have had to stop at the next inn for the night anyway. Don’t know how far that is, exactly. We might be quicker walking back to Truro.”

“But we left Truro more than two hours ago,” I exclaimed. “It was still light!”

“I saw a house through the trees,” Mrs. Darke said with her usual calm good sense. “I shall walk up there and ask for assistance.”

“You can’t go on your own,” I objected. “It’s pitch-dark.”

“I’ll take a lantern. Besides, I’m not afraid of the dark, and I have eyes like a cat,” she assured me.

“In that case, you can lead me,” I said. “John can wait with the horses.”

“Is that the best idea?” John asked doubtfully. Now that the horses were calm, he looked to Mrs. Darke for guidance. People tend to. In the two months she’d been my sisters’ governess, my whole family had come to rely on her for all sorts of things, even taking my mother’s place in accompanying me to Penderran where I was to meet my betrothed’s family. And yet she wasn’t so much older than me, a mere eight years or so, and she’d already been married, widowed, and was now engaged to be married once more, although how that fitted into her employment with us, my mother had yet to iron out.

“Yes, I believe it is,” Mrs. Darke said firmly. “Come along, Miss Goring.” Taking one of the coach lanterns from John, she set off along the muddy, uneven road, back the way we’d come.

Only then did I begin to notice the profound silence. I have spent most of my life in cities, where there is nearly always noise of some kind at all hours. Here, in rural Cornwall, the silence seemed to ring in my ears. All I could hear were our soft footsteps and my own breathing. In among the soft scents of grass and distant animals, I could smell the sea. Penderran was inland, but we still seemed to be hugging the coast.

“There,” Mrs. Darke said, pointing ahead to a road—well, a track—barely visible in the darkness, going up to the left towards the wood. When we got there and I lifted the lantern high, I could make out rows of blazing lights in a distant house. How could I have missed that?

“It must be huge,” I observed, continuing to walk. “Who lives there?”

“I have no idea.”

“Perhaps it’s the evil baronet who killed his family,” I said to tease her—or perhaps from curiosity to see if she could be frightened.

“Which evil baronet?” she asked, as though asking which shade of rose I preferred.

“The one the old crone at the inn was trying to scare us with. In Truro. What if this is his house?”

“Well, it’s unlikely he’d be there if he murdered his family.” She looked up at the sky. “Carnwyth,” she murmured thoughtfully.

“That was it.” I thought for a moment. “I saw a concert pianist in Rome on my seventeenth birthday who had the same name.”

“It will be the same man,” Mrs. Darke said casually.

I blinked at her and laughed. “You can’t possibly know that!”

“Sir Salvador Carnwyth,” she said. “His family was killed in their own home two years ago.”

I scowled at her. “Are you teasing me, Mrs. Darke?”

She looked surprised. “No, that’s quite true. But we have no reason to imagine this is his house, do we? And you know, you might consider calling me Barbara since I have no dignity to maintain on this journey.”

“It might be more comfortable,” I allowed. Actually, I was delighted by the friendship implied by being on first-name terms with the strangely exotic Barbara Darke. She was an excellent teacher, but an odd governess by most people’s standards, only I could never quite put my finger on how.

“I suspect the house belongs to a huge family,” she said. “Since there are so many lights on.”

I eyed the house with some misgivings now that we’d drawn nearer. Despite the lights, it looked ancient and bleak. I shivered. “Perhaps it’s haunted. The lights are to scare away the ghosts.”

“Don’t be silly, that’s what you have me for.”

I laughed. Two large stone gateposts loomed out of the darkness, an iron gate between them. Just beyond it was a small gatehouse, which was something of a relief to me—I’d had enough walking—until Barbara observed, “It’s ruined, by the look of things. We’ll have to go on to the main house.”

I pushed at the gate, which opened at once, although with a massive screech that seemed to echo around the countryside.

We walked on along a driveway that swept around in a great curve to the front of the house. It must once have been a gracious entranceway, but it was overgrown with weeds and some of the stones were loose or overturned so that we stumbled occasionally, even by the light of the lantern. Beside it, I could make out no garden or well-kept grounds, just an extension of the woods and overgrown weeds.

“A once great but now impoverished family,” I guessed.

“No wonder they’re impoverished, with all those lights.”

“Must you be so prosaic?”

“I thought you’d prefer it to tales of ghosts and murderers.”

I laughed again, but I’d already caught an unexpected sound that grew louder as we approached the house. Music. The notes of a piano. “Only listen, Barbara,” I hissed. “It is him! Or the ghosts of his dead family, perhaps…”

To my surprise—for I was only talking nonsense to entertain us both—Barbara shivered and made no answer. However, when I peered at her more closely, she showed no signs of distress, merely marched towards the front steps and the great door standing between two massive stone pillars. The music coming from inside was powerful, almost exquisite. Whoever played was a master.

I pulled the bell, half expecting the rope to come away in my hands. It didn’t, but since we heard no sign that it had actually rung inside the house, Barbara lifted the knocker and rapped loudly.

There was no pause in the piano, which went on rolling and building like a tide sweeping in to the shore. It made my spine tingle in a way that would have been pleasurable in a theatre. As it was, I found myself looking nervously around, imagining I saw figures flitting through the bushes beside what had once been a lawn. I even heard their rustling.

Barbara knocked again, longer and louder, and this time, the music cut off so abruptly that I was actually disappointed. Barbara knocked once more for good measure. In the deafening silence, we looked at each other. Although it was dark, it was not late and there should surely have been servants around to answer the door.

On the thought, hasty footsteps strode across a wooden floor, approaching the front door, which wrenched open so suddenly—and with such a screech of ill-kept hinges—that I actually jumped, throwing up an arm to protect my eyes from the blinding blaze of light within.

For an instant, all I saw was a tall, dark, faceless male figure in his shirtsleeves, framed in the doorway. I blinked, and his features swam into focus. Tousled black hair fell forward over a scowling face handsome enough to give even an engaged lady butterflies, despite the overall impression of unkemptness. His jaw was stubbly, without having a definite beard, and he wore no coat or waistcoat. His shirt seemed askew upon his person, carelessly open at the throat.

If surprise deprived us of words, at least we had the comfort of seeing the astonishment in the man’s wide, dark brown eyes.

“What?” he said, almost hoarsely, as if unused to speech.

“We’re sorry to disturb you,” Barbara said civilly. “Our coach has lost a wheel up on the road, and we were hoping for your assistance.”

His gaze, which seemed to have fixed on my face without blinking, flickered to her and then back to me. “What assistance?”

“Perhaps you have another conveyance we might borrow and send back to you from Penderran?” I suggested. “Or even from the next inn, wherever that might be.”

His frown deepened. “I have no vehicles here. I can give you a horse.”

“I’m afraid I can’t ride,” I confessed.

His gaze, which had flickered to Barbara again, swung back on me. “Why not?”

I blinked. “I suppose I never had time to learn.” But at last it struck me that his voice and accent were those of a gentleman. We weren’t addressing a servant here, whatever his appearance.

Unexpectedly, a smile glimmered in his rather wild eyes. “And it seems I don’t have time to teach you.” He glanced up at the impenetrable sky. “It’s going to pour. Where are your friends? Do you have no escort?”

“We left our coachman on the road with the horses.”

The young man appeared to hesitate, his brow lowered in annoyance. “You can’t wait here. I have no female servants. Or anyone who can mend your coach in the dark.”

I lifted my chin. “We do not ask—”

“We don’t need servants,” Barbara interrupted. “A room in which to sit undisturbed until morning would suffice. If you’d be so good.”

The man’s eyes narrowed. He didn’t seem intimidated by her, as people often were, but neither was he remotely pleased with her proposal. At last, he yelled, “Jack!” and stood back from the door in a grudging kind of a way.

Taking my arm, Barbara marched us inside. A slovenly looking servant emerged from the shadowy depths beyond the blaze of candlelight, blinking at Barbara and me in clear astonishment.

“Give these ladies tea, or something,” our host instructed. “I’m going to see to their horses.” With that, he seized some garment—perhaps a coat or a jerkin, I couldn’t make it out—and strode out of the open door, slamming it behind him.

The servant, Jack, regarded us, scratching his head. “You’d better come up here,” he said at last, turning to walk towards the wide, curving staircase.

I had to force myself not to take Barbara’s hand like a nervous schoolgirl. Despite the brightness of the hundreds of candles, the inside of the house screamed neglect. Dust sparkled in the air and lay thickly on the floors, lamps, and what was probably a beautifully carved wooden bannister. The eyes of presumably dead ancestors glared at us from within heavy, ornate frames dulled by dust and cobwebs.

On the first-floor landing, Jack led us across a wide hall into a gracious room of medium size, dominated by a grand piano. My spirits lifted at sight of it, for I have always loved music. Besides, the dust in here seemed a little less thick and the room itself a little more lived-in than the neglected halls and stairs. A coat lay over the back of a sofa and a half-drunk glass of red wine resided on the table next to it.

“Tea,” Jack uttered with the same contempt he might have said “poison,” and slouched out of the room again.

“I almost feel I should make it for him,” Barbara murmured.

“Surely there must be more servants downstairs?” I said optimistically.

“Doesn’t look it to me,” Barbara said, running her finger along the back edge of the piano. “I wonder if he lights all those candles himself?”

“It would take him hours! There can’t be any women in his family,” I added, glancing with disfavour at a torn cushion cover and a dusty chair arm.

“I’m not sure there’s anyone in his family—not living here, at any rate.”

“What makes you say so?” For some reason, I didn’t want to think of him living in this bleak house alone save for the surly servant. “I’m sure Robert and his friends would live like this if they were allowed. I’m not sure he’d notice.”

Robert was the eldest of my brothers, preparing for the entrance examination to university. At least that was my parents’ hope, but he was easy-going to a fault. We never understood how he managed to pass any examinations at all.

“He’d notice the contrast,” Barbara argued. “Our host has got used to this. I wonder why?”

“He doesn’t seem to like people,” I said, oddly disappointed by the observation.

“He certainly isn’t welcoming,” Barbara allowed. “Not necessarily the same thing.”

“Perhaps he’s ashamed of the mess.”

“Perhaps.” Barbara’s eyes were fixed on a point near the fireplace, where the dying embers of a fire glowed feebly. I could see nothing to account for her interest. I brushed past her and sat down in the chair closest to the fire, stretching my hands out towards it. Looking around her rather than at where she was going, Barbara followed me and sank into the chair opposite.

A few minutes later, we heard the servant clump his way back upstairs. For some reason, I found the sound ridiculous to the point of humorous and had to drag my gaze free of Barbara’s to avoid laughing.

Jack came into the room carrying a tarnished silver tray on which resided a fine teapot, two matching cups and saucers, a dainty cream jug, and a sugar bowl with tongs. After laying the tray down on the large table by the door, he brought a smaller table and placed it beside us before bringing the tray.

Barbara and I exchanged impressed glances, but this, apparently, was the height of Jack’s manners, for having deposited the tray, he simply shambled off without another word.

Or at least, he would have, had Barbara not called to him, “Thank you! Surely you are not the only servant in so large a house?”

The man paused grudgingly. “No.”

Barbara leaned forward and lifted the teapot. “And is it just your master—the man who let us in—who lives here? Of the family, I mean.”

“Yes,” Jack replied. Clearly, extracting information, let alone gossip, about our host was not going to be easy.

“What is this place?” I asked bluntly.

“Trellyn,” Jack answered readily enough while I accepted my cup of tea from Barbara. “Trellyn House, this be.”

“Ah. And then, your master is…?”

“Sir Salvador Carnwyth,” Jack said shortly and stumped off out of the room.

My eyes widened as they flew to meet Barbara’s gaze. “My God, it is him! Were you serious when you said the pianist Carnwyth is the same man whose family was murdered in their home?”

If I expected Barbara to reassure me, I was doomed to disappointment. She nodded with a grimness I had never seen in her before. “Oh, yes. How many Salvador Carnwyths do you imagine there are?”

“My God,” I said slowly. “No wonder he doesn’t want strangers here.”

Again, she dragged her wandering gaze back to me, as though I were an object of unexpected curiosity. “Is that all?” she asked. “No we must flee this place before we’re murdered?”

I thought about it. “I’m not sure he’d give us tea if he meant to murder us.”

“And yet…he’s not quite stable, is he?”

I shrugged. “I doubt I would be if someone killed my entire family and I then lived alone in this musty mausoleum. Even with every candle lit.”

“And if you’d killed them yourself?” Barbara enquired.

“Do you think he did?” I asked breathlessly.

“I don’t know, but you sound as if you feel sorry for him.”

“I suppose I shouldn’t if he is the murderer,” I agreed. “Only, as you said, why would he still be here if he was the killer? He’d be hanged.”

“You believe him to be harmless?” Barbara asked.

I shifted in my chair. Did I? “Do you?” I countered.

Barbara sipped her tea. “No, I don’t think he’s harmless at all.”

I stared at her, my stomach twisting. “You believe he did it? And we’re sitting here drinking his tea?”

“I didn’t say that. I said he isn’t harmless. I’ve rarely come across a man so angry and so churned up, and yet so determined.”

“So determined in what?”

“How would I know?” Barbara asked, replacing her cup in the saucer in her lap.

“You seem to know everything else,” I retorted.

“I’m good at recognising emotion,” she said. “And none of his was directed at us—except minor irritation, perhaps. And curiosity.”

“And so we drink his tea,” I said, toasting her with my cup.

She smiled at me with approval. However, behind my willingness to banter with her, my mind was churning, dredging up the story the old woman had told us in Truro, and remembering every expression I’d seen on his face during our short encounter. My heart ached for the awfulness of what had happened to him, quite aside from the fear of his guilt. And it all swirled around my head to the sound of the turbulent music he’d been playing when we arrived. A man who could make music like that was capable of anything.